Reaching Your Goals, Art Baker's Life In Sports

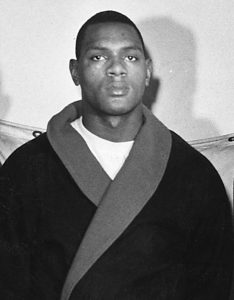

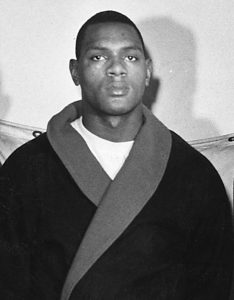

The pinkie finger on his left hand turns slightly to the left, evidence of a life that certainly saw its share of violent clashes in the arena. Other than that, there aren’t a lot of outward signs that might suggest that the man who drives a bus a couple of days per week is anything more than just another Joe.

Recently he had to go have an eye exam and a checkup. They make you do that a little more often when you’re 75 years old, driving a bus. Wait, what? How is this man three-quarters of the way to a century? He barely looks like he’s halfway there, but there’s not much about Art Baker that doesn’t grab your attention.

A couple of times per week, he’s up at the Falmouth Sports Center pushing plates up and down that men half his age would struggle with. While they wear their pretty track suits and brand name workout wear, he’s got on old fashioned sweats, because that’s what he is there to do. He’s lost 50 pounds since Thanksgiving, and now he looks like he could find the hole between the guard and tackle and break a big gainer.

He doesn’t put up the 445-pounds that he used to, nor can he push out the same number of reps, but there’s no shame in that. He was once one of the best athletes in the country, and that’s a statement that’s not up for debate.

A little over 50 years ago, Baker was a first-round draft pick of both the Philadelphia Eagles and Buffalo Bills after a standout career at Syracuse University, where he helped the Orange win a national championship in 1959, and then went on to win the NCAA championship in wrestling that year as well, becoming the first athlete to ever win a team sport and individual sport championship in the same school year. With the American and National Football Leagues having not yet joined as one, a bidding war ensued. Buffalo offered more money, so it was the Bills jersey he donned. He spent a couple of years there before going on to play in the Canadian Football League, in Hamilton and Calgary. His playing days were over in 1966, but that was just the end of a chapter for the Erie, Pennsylvania, native. Baker went on to make a very comfortable living as an ad executive in the mid-Atlantic region of the country, where he was considered one of the top salesmen in the United States.

A little over 50 years ago, Baker was a first-round draft pick of both the Philadelphia Eagles and Buffalo Bills after a standout career at Syracuse University, where he helped the Orange win a national championship in 1959, and then went on to win the NCAA championship in wrestling that year as well, becoming the first athlete to ever win a team sport and individual sport championship in the same school year. With the American and National Football Leagues having not yet joined as one, a bidding war ensued. Buffalo offered more money, so it was the Bills jersey he donned. He spent a couple of years there before going on to play in the Canadian Football League, in Hamilton and Calgary. His playing days were over in 1966, but that was just the end of a chapter for the Erie, Pennsylvania, native. Baker went on to make a very comfortable living as an ad executive in the mid-Atlantic region of the country, where he was considered one of the top salesmen in the United States.

When it was time to retire, most of his contemporaries packed up to head south for the golf courses. Art Baker prefers fish to birdies, so he trekked north to be on the water where he could land stripers. Having settled in Mashpee, Baker spends countless hours casting along the canal and beaches, pulling in trophy fish.

It was in Erie where Baker first grabbed the attention of people that notice athletes, and it wasn’t just on the football field. Baker was an exceptional running back and defensive back in his high school days, but football wasn’t his best sport. Not by a long shot.

Wrestling was where he truly made a name for himself.

People don’t believe Baker when he tells them that himself. “They’re like, you were a first-round draft pick, you won the NCAA championship, you played in the NFL, that can’t be true,” he said. “And I tell them, what I did in wrestling dwarfs all that.”

And it all started because as a teenager, he was looking for something to do when football ended.

“I popped my head in the wrestling room,” he said. “I was too short to play basketball, too slow to be a swimmer. I wanted a winter sport.”

But wrestling? “There were no black wrestlers, period,” he said.

He was drawn to the sport, despite the fact that no one else in the room looked like him. He watched what was going on, and believed that he was capable of doing it. “I thought I could do this, but then here come the detractors,” he said. “I said, ‘I’m going out for the team and I’m going to be the first black state champion.’ Everybody laughed at me. That was the first goal I made in sports, ‘I’m going to be the first ever black 4x state champion in Pennsylvania’.”

Not everyone laughed. Coach Tony Verga, who had been a state champion himself less than a decade earlier (1940), took Baker under his wing and helped guide him to greatness. Baker said that some of his teammates didn’t want anything to do with him, and that he was an outsider because of his skin color, even though he was clearly the best wrestler in his weight class at a young age. He spent a lot of time with Verga, learning his craft, and the love for the sport took hold despite outside distractions. “As an 8th grader, I couldn’t wrestle varsity, so I was on the JV team. I was the best wrestler in my weight class and I started to really love it,” Baker recalled.

He loved the sport, and he wanted to get better. Just like today, back then there were specialized athletic camps that could really turn a decent athlete into a good one, and give a great one an extra edge. Such a camp was available for Baker, but it cost money to go, money he didn’t have.

“It was a week-long camp, and it cost $59. I didn’t have $59. I came up with $20 and worked downtown, I cleaned up a store, and my boss knew me from the inside out. He knew I was a good kid. He knew that this wrestling camp was very important to me, so without telling me, he went up and down the street in my hometown and collected money from these business men. He asked me the week before the camp if I was going. And I told him I only had 20 bucks, and I didn’t think so. He said, ‘Well, I’ve got good news for you. You’re going.’ I told him I didn’t have the money and he said, ‘everybody on State Street collected this money.’ It was $62, plus I still had my 20. I had more than enough, I could eat steak dinner every night.”

“From that moment on, my whole persona changed. I started to look at white people from a totally different perspective,” Baker said.

Those businessmen that helped pay his way to the camp became his biggest fans. They attended all of his matches, and rooted him on to victory after victory. “Every time I’d go out on the mat, I’d look over to them and say ‘thank you.’ Without them, there’d be no me.”

The camp’s administrator, Charlie Speidel, hooked Baker up with a wrestler to work with named Dave Adams, a wrestler from Penn State who was the EIWA champion and NCAA runner-up at 145 pounds. The duo beat up on one another for a week, and Baker said that Adams filled him with confidence at the end of the experience. “He said ‘after working out with you for this week, Art, you’re not only going to be the first black kid to win multiple state titles in Pennsylvania, but you’re going to win multiple titles at the next level. I’m doing everything I can to hold my own.”

Baker did win multiple high school titles, and probably should have had a third. He was undefeated as a sophomore, but his coach signed him up for a weight class that he didn’t qualify for. Even though he hadn’t lost all year, he wasn’t able to get down to 145 pounds for the state tourney, and he was a spectator.

That coach was let go from the position the following year.

The man that replaced him was fresh out of college, named Jerry Mowry (Maurey). Baker went head-to-head with his new coach every day in practice, and left frustrated for more than half the year. “I couldn’t score a point on him, and I’m good,” he said. “On the 18th of January, I scored my first point on him. I got a point escape on him. He stopped the match and said, ‘Okay. You don’t know who am I, do you?’”

Mowry (Maurey) was a decorated wrestler from Penn State, who had won three EIWA championships and placed twice in the NCAA tournament for the Nittany Lions.

“Every day, you come here and I clean your clock and you keep getting tougher and tougher and tougher. There’s no quit in you,” Baker recalled Mowry saying. “He said, ‘there is nobody in the country that can probably beat you in high school. If I can’t beat you, there’s no one in high school that is going to beat you.’ From that point on, I lost one match, and that was in the district tournament... from that point forward until I left Syracuse, I never lost another match. Everything I ever did in football, wrestling just dwarfs it.”

He lost just once in all of his high school career, early on to a wrestler named Tomczack. “He pinned me, and I was ahead of him on points, and when I walked off the mat, I said, ‘I will never, ever lose another wrestling match.’”

Those words were bold, but also ones that he stood by and followed through on. And that loss, would prove pivotal later on.

Every season in college, Baker would come late into the season—since the Orange were always involved in a bowl game—and jump right into the wrestling world. He’d wrestle matches at a higher weight class until he was able to trim down to where he belonged as a wrestler, which was 191 pounds. Despite having had to grapple at a higher weight class that entire year, when it was time for the rankings for the 191-division to be listed for the NCAA tournament, Baker came in seeded number one.

His run to the title could not have been scripted better by Hollywood. His first-round opponent was an athlete of nearly equal stature, who went on to play in the NFL as well—Marion Rushing of Southern Illinois.

Rushing gave Baker his closest collegiate match, a 4-1 decision that went to the wire. “If I’d taken anyone for granted, I probably would have lost that match, but I wasn’t going to do that because I’m representing those five guys [from Erie] and my family,” Baker said.

In the semifinals, Baker found himself in a position he was unfamiliar with, behind in points against Gordon Trapp, of Iowa, who was wrestling on his home turf. Despite being up against a superb wrestler in hostile territory, Baker rallied for a 9-6 victory that put him into the finals.

The Iowa fans may have hated Baker during the semis, but they had his back in the championship round. Tim Woodin, the other favorite in the 191-pound division, was his opponent, and Woodin hailed from Michigan State, one of Iowa’s biggest rivals. The wrestler from Syracuse had himself a fan base, but more importantly a chance to fulfill a dream he’d been building toward for the better part of a decade.

His coach approached Baker prior to the match, but the wrestler told him he didn’t need to be motivated. “I told him, ‘Here’s what I want you to do. Sit over there where the coaches sit and I want you to see if you can see any weakness in my opponent’s game, but as far as motivation, I’ve been preparing for this moment since the 8th grade. There is nothing that you could do, or say to me that can get me any higher than I am right now.’ You see, this was the fulfillment of my goal, this was my goal since the 8th grade. ‘I’m exactly where I want to be and the time is right. All I have to do is walk through that door. The door is opening and I’m going to make history here in the next nine minutes.’”

“I said, ‘You with that?’ and he said, ‘I got it, Art.’”

“I walked out, shook hands with my opponent, Woodin, and I said, ‘I hate to tell you this, young man, but I’m going to be the first brother to win this.’ I had a little Ali in me... ‘you’re going down, man.’”

Baker dreamed of becoming the first African-American NCAA wrestling champ. He thought that he was, but discovered later that he was the second. Simon Roberts of San Diego State had won at the 147-pound limit two years earlier.

That someone else had gotten there first didn’t matter at the end, though. Baker looks back at the young man he was, and smiles with pride.

“Any time you set a goal, no matter how big, and you get there, that’s what it’s all about.”

Recently he had to go have an eye exam and a checkup. They make you do that a little more often when you’re 75 years old, driving a bus. Wait, what? How is this man three-quarters of the way to a century? He barely looks like he’s halfway there, but there’s not much about Art Baker that doesn’t grab your attention.

A couple of times per week, he’s up at the Falmouth Sports Center pushing plates up and down that men half his age would struggle with. While they wear their pretty track suits and brand name workout wear, he’s got on old fashioned sweats, because that’s what he is there to do. He’s lost 50 pounds since Thanksgiving, and now he looks like he could find the hole between the guard and tackle and break a big gainer.

He doesn’t put up the 445-pounds that he used to, nor can he push out the same number of reps, but there’s no shame in that. He was once one of the best athletes in the country, and that’s a statement that’s not up for debate.

A little over 50 years ago, Baker was a first-round draft pick of both the Philadelphia Eagles and Buffalo Bills after a standout career at Syracuse University, where he helped the Orange win a national championship in 1959, and then went on to win the NCAA championship in wrestling that year as well, becoming the first athlete to ever win a team sport and individual sport championship in the same school year. With the American and National Football Leagues having not yet joined as one, a bidding war ensued. Buffalo offered more money, so it was the Bills jersey he donned. He spent a couple of years there before going on to play in the Canadian Football League, in Hamilton and Calgary. His playing days were over in 1966, but that was just the end of a chapter for the Erie, Pennsylvania, native. Baker went on to make a very comfortable living as an ad executive in the mid-Atlantic region of the country, where he was considered one of the top salesmen in the United States.

A little over 50 years ago, Baker was a first-round draft pick of both the Philadelphia Eagles and Buffalo Bills after a standout career at Syracuse University, where he helped the Orange win a national championship in 1959, and then went on to win the NCAA championship in wrestling that year as well, becoming the first athlete to ever win a team sport and individual sport championship in the same school year. With the American and National Football Leagues having not yet joined as one, a bidding war ensued. Buffalo offered more money, so it was the Bills jersey he donned. He spent a couple of years there before going on to play in the Canadian Football League, in Hamilton and Calgary. His playing days were over in 1966, but that was just the end of a chapter for the Erie, Pennsylvania, native. Baker went on to make a very comfortable living as an ad executive in the mid-Atlantic region of the country, where he was considered one of the top salesmen in the United States.When it was time to retire, most of his contemporaries packed up to head south for the golf courses. Art Baker prefers fish to birdies, so he trekked north to be on the water where he could land stripers. Having settled in Mashpee, Baker spends countless hours casting along the canal and beaches, pulling in trophy fish.

It was in Erie where Baker first grabbed the attention of people that notice athletes, and it wasn’t just on the football field. Baker was an exceptional running back and defensive back in his high school days, but football wasn’t his best sport. Not by a long shot.

Wrestling was where he truly made a name for himself.

People don’t believe Baker when he tells them that himself. “They’re like, you were a first-round draft pick, you won the NCAA championship, you played in the NFL, that can’t be true,” he said. “And I tell them, what I did in wrestling dwarfs all that.”

And it all started because as a teenager, he was looking for something to do when football ended.

“I popped my head in the wrestling room,” he said. “I was too short to play basketball, too slow to be a swimmer. I wanted a winter sport.”

But wrestling? “There were no black wrestlers, period,” he said.

He was drawn to the sport, despite the fact that no one else in the room looked like him. He watched what was going on, and believed that he was capable of doing it. “I thought I could do this, but then here come the detractors,” he said. “I said, ‘I’m going out for the team and I’m going to be the first black state champion.’ Everybody laughed at me. That was the first goal I made in sports, ‘I’m going to be the first ever black 4x state champion in Pennsylvania’.”

Not everyone laughed. Coach Tony Verga, who had been a state champion himself less than a decade earlier (1940), took Baker under his wing and helped guide him to greatness. Baker said that some of his teammates didn’t want anything to do with him, and that he was an outsider because of his skin color, even though he was clearly the best wrestler in his weight class at a young age. He spent a lot of time with Verga, learning his craft, and the love for the sport took hold despite outside distractions. “As an 8th grader, I couldn’t wrestle varsity, so I was on the JV team. I was the best wrestler in my weight class and I started to really love it,” Baker recalled.

He loved the sport, and he wanted to get better. Just like today, back then there were specialized athletic camps that could really turn a decent athlete into a good one, and give a great one an extra edge. Such a camp was available for Baker, but it cost money to go, money he didn’t have.

“It was a week-long camp, and it cost $59. I didn’t have $59. I came up with $20 and worked downtown, I cleaned up a store, and my boss knew me from the inside out. He knew I was a good kid. He knew that this wrestling camp was very important to me, so without telling me, he went up and down the street in my hometown and collected money from these business men. He asked me the week before the camp if I was going. And I told him I only had 20 bucks, and I didn’t think so. He said, ‘Well, I’ve got good news for you. You’re going.’ I told him I didn’t have the money and he said, ‘everybody on State Street collected this money.’ It was $62, plus I still had my 20. I had more than enough, I could eat steak dinner every night.”

“From that moment on, my whole persona changed. I started to look at white people from a totally different perspective,” Baker said.

Those businessmen that helped pay his way to the camp became his biggest fans. They attended all of his matches, and rooted him on to victory after victory. “Every time I’d go out on the mat, I’d look over to them and say ‘thank you.’ Without them, there’d be no me.”

The camp’s administrator, Charlie Speidel, hooked Baker up with a wrestler to work with named Dave Adams, a wrestler from Penn State who was the EIWA champion and NCAA runner-up at 145 pounds. The duo beat up on one another for a week, and Baker said that Adams filled him with confidence at the end of the experience. “He said ‘after working out with you for this week, Art, you’re not only going to be the first black kid to win multiple state titles in Pennsylvania, but you’re going to win multiple titles at the next level. I’m doing everything I can to hold my own.”

Baker did win multiple high school titles, and probably should have had a third. He was undefeated as a sophomore, but his coach signed him up for a weight class that he didn’t qualify for. Even though he hadn’t lost all year, he wasn’t able to get down to 145 pounds for the state tourney, and he was a spectator.

That coach was let go from the position the following year.

The man that replaced him was fresh out of college, named Jerry Mowry (Maurey). Baker went head-to-head with his new coach every day in practice, and left frustrated for more than half the year. “I couldn’t score a point on him, and I’m good,” he said. “On the 18th of January, I scored my first point on him. I got a point escape on him. He stopped the match and said, ‘Okay. You don’t know who am I, do you?’”

Mowry (Maurey) was a decorated wrestler from Penn State, who had won three EIWA championships and placed twice in the NCAA tournament for the Nittany Lions.

“Every day, you come here and I clean your clock and you keep getting tougher and tougher and tougher. There’s no quit in you,” Baker recalled Mowry saying. “He said, ‘there is nobody in the country that can probably beat you in high school. If I can’t beat you, there’s no one in high school that is going to beat you.’ From that point on, I lost one match, and that was in the district tournament... from that point forward until I left Syracuse, I never lost another match. Everything I ever did in football, wrestling just dwarfs it.”

He lost just once in all of his high school career, early on to a wrestler named Tomczack. “He pinned me, and I was ahead of him on points, and when I walked off the mat, I said, ‘I will never, ever lose another wrestling match.’”

Those words were bold, but also ones that he stood by and followed through on. And that loss, would prove pivotal later on.

Every season in college, Baker would come late into the season—since the Orange were always involved in a bowl game—and jump right into the wrestling world. He’d wrestle matches at a higher weight class until he was able to trim down to where he belonged as a wrestler, which was 191 pounds. Despite having had to grapple at a higher weight class that entire year, when it was time for the rankings for the 191-division to be listed for the NCAA tournament, Baker came in seeded number one.

His run to the title could not have been scripted better by Hollywood. His first-round opponent was an athlete of nearly equal stature, who went on to play in the NFL as well—Marion Rushing of Southern Illinois.

Rushing gave Baker his closest collegiate match, a 4-1 decision that went to the wire. “If I’d taken anyone for granted, I probably would have lost that match, but I wasn’t going to do that because I’m representing those five guys [from Erie] and my family,” Baker said.

In the semifinals, Baker found himself in a position he was unfamiliar with, behind in points against Gordon Trapp, of Iowa, who was wrestling on his home turf. Despite being up against a superb wrestler in hostile territory, Baker rallied for a 9-6 victory that put him into the finals.

The Iowa fans may have hated Baker during the semis, but they had his back in the championship round. Tim Woodin, the other favorite in the 191-pound division, was his opponent, and Woodin hailed from Michigan State, one of Iowa’s biggest rivals. The wrestler from Syracuse had himself a fan base, but more importantly a chance to fulfill a dream he’d been building toward for the better part of a decade.

His coach approached Baker prior to the match, but the wrestler told him he didn’t need to be motivated. “I told him, ‘Here’s what I want you to do. Sit over there where the coaches sit and I want you to see if you can see any weakness in my opponent’s game, but as far as motivation, I’ve been preparing for this moment since the 8th grade. There is nothing that you could do, or say to me that can get me any higher than I am right now.’ You see, this was the fulfillment of my goal, this was my goal since the 8th grade. ‘I’m exactly where I want to be and the time is right. All I have to do is walk through that door. The door is opening and I’m going to make history here in the next nine minutes.’”

“I said, ‘You with that?’ and he said, ‘I got it, Art.’”

“I walked out, shook hands with my opponent, Woodin, and I said, ‘I hate to tell you this, young man, but I’m going to be the first brother to win this.’ I had a little Ali in me... ‘you’re going down, man.’”

Baker dreamed of becoming the first African-American NCAA wrestling champ. He thought that he was, but discovered later that he was the second. Simon Roberts of San Diego State had won at the 147-pound limit two years earlier.

That someone else had gotten there first didn’t matter at the end, though. Baker looks back at the young man he was, and smiles with pride.

“Any time you set a goal, no matter how big, and you get there, that’s what it’s all about.”